bhm reading list (2020)

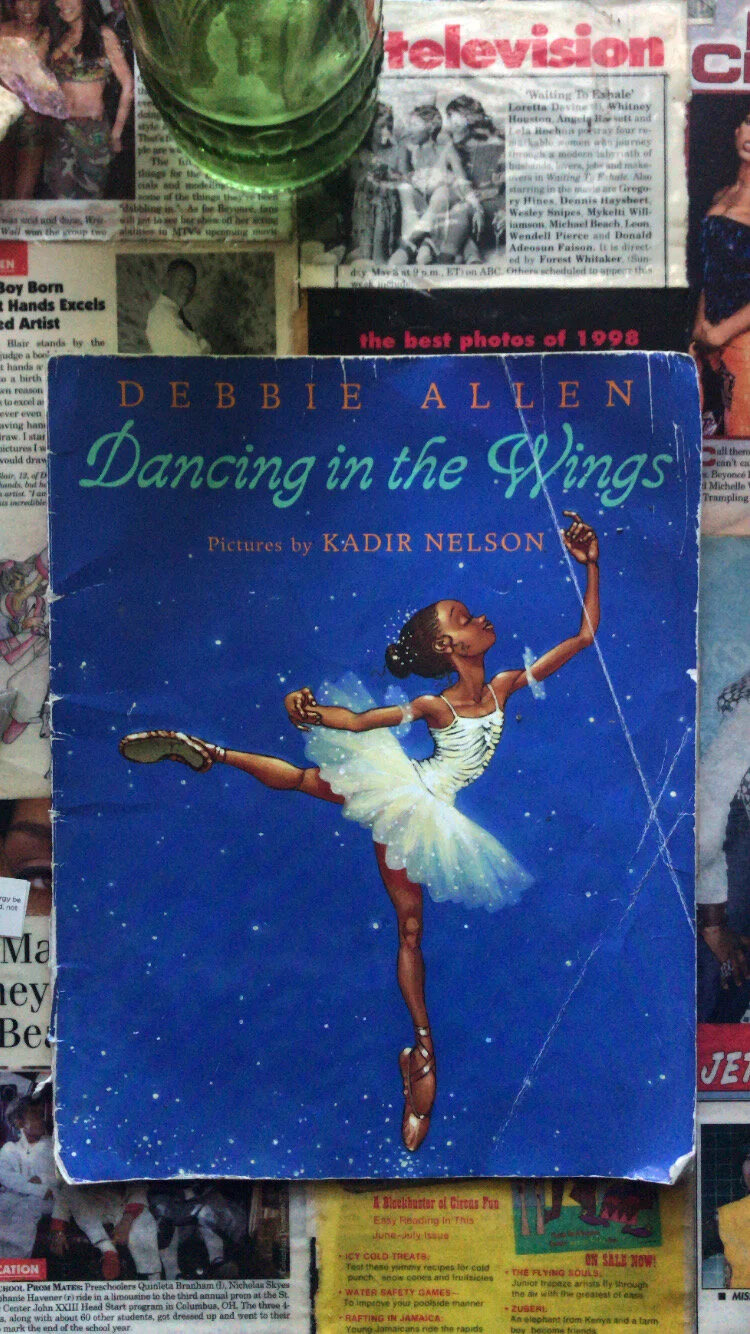

Dancing in the Wings by Debbie Allen

in this collection of plays you can find both The Bronx is Next and Uh Huh But How Do It Free Us

The Black Woman: An Anthology by Toni Cade

as promised, february faves.

What the Negro Wants by Rayford W. Logan

I am Black (you have to be willing to not know) by Thomas F. DeFrantz

The Education of Black People by W. E. B. Du Bois

Dancing in the Wings by Debbie Allen

Day of Absence by Douglas Turner Ward

Criteria of Negro Art by W. E. B. Du Bois

Bootycandy by Robert O’Hara

for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange

Intimate Apparel by Lynn Nottage

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual by Harold Cruse

She Come Bringing Me That Little Baby Girl by Eloise Greenfield

Liberty Deferred by Abram Hill and John D. Silvera

Uh Huh But How Do It Free Us by Sonia Sanchez

salt by Nayyirah Waheed

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Black Drama of the Federal Theatre Era by E. Quita Craig

Fabulation, or the Re-Education of Undine by Lynn Nottage

Red Light, Green Light Mama and Me by Cari Best

Native Son by Nambi E. Kelley

Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois

The Bronx is Next by Sonia Sanchez

Black Means… by Gladys Groom and Barney Grossman

Mis-education of the Negro by Carter G. Woodson

Vigil: Poems by Chiyuma Elliott

The Black Woman: An Anthology by Toni Cade

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson

On Strivers Row by Abram Hill

Citrus by Celeste Jennings

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual by Harold Cruse

Mis-education of the Negro by Carter G. Woodson

'Native Son'

‘Native Son’ is about the humanization of Black people. yet, as I sat in the audience of a talkback following PlayMakers’s production of the piece, I realized that many of the audience members and actors seemed to have missed the point.

the play was written by Nambi E. Kelley, and is an adaptation of Richard Wright’s 1939 novel of the same name. ‘Native Son’ was originally adapted for the stage by Paul Green, whose drastic and unnecessary changes to the text altered the entire meaning and intent of the piece for audiences in 1942. Kelley’s version, however, maintains Wright’s intent, and does so in a way that is both powerful and beautiful.

this review is about digestion.

as usual, the audience of PlayMakers was predominately white and elderly, but today, there were small pockets of undergraduate students. these students were easily identifiable by their lazy, ‘just woke up’ fashions, and incessant need to check their phones during the show. their attendance to this play was clearly out of necessity or requirement, rather than desire. I don’t think they understood the play’s urgency and relevancy, and I don’t think PlayMakers, nor the professors who required them to see it, care.

within the first ten minutes of the show we see a drunk white woman named Mary stumble on the stage and plead for the help and attention of a Black man, Bigger Thomas. Mary is played by Sarah Elizabeth Keyes, and Bigger Thomas is portrayed by Brandon Herman St. Clair Haynes. as Mary flirts and attempts to seduce Bigger in her drunken state, the audience giggles—but the play is set in the 1930s and interracial relations at this time are no laughing matter. this particular scene serves as the critical point of attack for the play, and is rather ominous because of the implications it has. this is the scene in which Mary dies, and though Bigger did not kill her, the optics of the situation automatically incriminate him. the play shows Bigger’s struggle with finding a solution to this problem, and in his attempt to save himself, he does nothing but make the situation worse.

Kelley’s version of this play brilliantly shows Bigger’s desperation. she manages to emphasize his humanity and give validity to his behavior by her use of his personified conscience, The Black Rat, played by Brandon J. Pierce.

I felt empowered by this piece. moved. overwhelmed. untouchable. Haynes’s performance was one of the best I’ve ever seen at PlayMakers, and Kelley’s writing was impeccable.

but it was clear that those bringing this play to life and other audience members may not have seen things the way I did.

I wondered if Keyes and the costume designer, Bobbi Owen, understood the over-the-top, yet disposable nature of the character Mary. Mary says the word ‘bigger’ a lot in the play, both in a suggestive sexual manner and when calling Bigger by his name. as a playwright and a trained actor, I know that repetition in a script is something that should be handled with care because it is usually being used to articulate a point. I think the severity of Mary’s actions would have been more poignant if Keyes had approached the language of the play more thoughtfully.

in the case of the costume designer, the attention given to Mary’s costumes versus those of Bessie and Vera say it all. there is a rather elaborate costume change at the beginning of the play in which Mary changes into a ‘jungle’ outfit, and honestly, I wished that effort was placed elsewhere. Davis, who in addition to Bessie also plays Bigger’s younger sister Vera, would have benefitted tremendously from an actual costume change instead of simply taking off her socks and switching her wig to communicate a difference in characters. I’m almost certain that this disparity was not intentional, however it continues to emphasize another large theme in the play: nobody cares about Black women.

and the audience members didn’t seem to either. I watched the white women sitting on the other side of the thrust stage cringe and cover their faces as Bigger used an axe to make Mary’s already dead body fit into a furnace. yet, when Bessie is raped, and has her head smashed in with a brick— a scene I found far more graphic than that of Mary’s mangling— these same women were stoic. no one seemed to care.

during the talkback, there were questions about the language of the play clearly directed toward the white actors and implying uncomfortability with using the ’n-word,’ yet none of them felt the need to speak or even acknowledge what was being asked. the cast was literally segregated on the stage and white women in the audience aggressively attempted to instruct Haynes on using a microphone, belittling him as he answered questions. it was as if they didn’t see the play at all.

they seemed to have missed the moments in the play where seemingly good intentions manifested as negative experiences and resulted in pain.

they seemed to have missed the humanity in Bigger Thomas, and how Bigger Thomas is a direct result of being Black in America.

they seemed to have missed that Bigger Thomas isn't just a character in a 1930’s novel, but someone who still exists today, simply trying to make a way where there isn’t one.

they seemed to have ingested the play like the kid who sat beside me—distracted, and on his phone.

'No Fear & Blues Long Gone: Nina Simone'

on August 25, 2019 in Hillsborough, NC, there was a KKK rally. down the road, and around the same time, in Chapel Hill, NC, I had the privilege of watching a musical about Nina Simone. the play was produced by Playmakers Repertory Company on the campus of UNC Chapel Hill.

UNC Chapel Hill, where a history of racism and discrimination is embedded in every building and white students burn cars in the street after winning basketball games.

but this isn’t about UNC. that was just for context. this is about Nina.

this production is the second I’ve seen in what I like to think of as ‘Nina Simone Week’ in North Carolina. ‘No Fear & Blues Long Gone: Nina Simone’ was written by Howard L. Craft and directed by Kathryn Hunter-Williams.

Yolanda Rabun takes on the role of Nina.

the play opens with the audience interaction Nina Simone is known for. Nina appears in the back of the house and works her way to the stage singing ‘Do I Move You.’ when she reaches the stage, she tells us about what we are going to see during the play, explaining that it is not about what she has done, but why.

I followed Nina’s journey by denoting beats in the show. we start where every Nina Simone story does, with Eunice Waymon in Tryon, NC. from there, we dissect the name ‘Nina Simone’ and swiftly move pass a brief mention of her bipolar disorder to ‘the notion or desire of freedom.’

although the play highlighted an early diagnosis in her youth, Nina’s mental health was not a real discussion point. this concerned me, because from my understanding, Nina’s bipolar disorder played a major role in her life, especially as she became more successful in her career. the show has a sort of ‘stream of consciousness’ structure, that alludes to her train of thought being affected by the disorder, but there is no real focus on how it impacted her life. I do think, however, that if Nina’s mental health was emphasized, the tone of the play would change and it may become less about the ‘why’ and more about the ‘what.’ still, I think it would be an interesting take.

‘the notion/desire of freedom’ calls for audience participation and Nina poses the question “what does freedom look like?” this marked a shift in audience interaction. three people spoke and that was only after Nina shamed the audience for not speaking up. in this moment, the spotlight moved from Nina to the audience and crossed the line of audience participation, forcing audience members to become part of the show whether they wanted to or not.

the show moves into another beat, exploring the theme of ‘submission’ as Nina talks about her second husband. and then, she gets on Twitter.

yes. Nina gets on Twitter.

I didn’t really like this part. she begins to talk about her messages on Twitter and an event organizing function it provides that I’ve never even heard of. Nina makes a cheeky joke about Tupac’s nose ring and rambles about going to a party at Langston’s— and I don’t think the latter would be so odd, if it had not been arranged via Twitter. Tupac, however, is an obscure talking point for a woman of Nina’s stature, especially when she was clearly repulsed by hip hop music in a previous scene. I think the playwright may have been making a point about Tupac’s intellect by putting him in discussion with historical literary figures such as Langston Hughes, Lorraine Hansberry, and James Baldwin, but I don’t think it made much sense for Nina to be even remotely interested Tupac’s presence. Nina did outlive Tupac, so there may be some dramaturgical evidence to support her desire to see him and his nose ring, but without that context, it seems strange.

from Twitter, Nina moves to ‘rage’ and then to ‘power,’ marking a dramatic shift in her music.

‘rage’ was my favorite. the use of light throughout the piece was very powerful and intentional, and this was no exception. Nina tells us about the Alabama church bombing in 1963 that killed four little girls, and four spotlights appear on the stage. it was beautifully done, and followed with Nina demanding that the audience say their names. though I’m still not sold on the need for audience participation, I thought it was a very poignant moment and a very necessary moment given what else was happening in North Carolina that day.

during ‘power,’ we take a very, very short imaginary car ride to Liberia, and arrive on the topic of sacrifice as it relates to taking a stand. this is another audience participation moment, and one that I strongly think should be reconsidered. Nina asks the audience for a name, referring to man who plays football and kneels, and a voice from behind me shouts out, “colon!”

I can only imagine what, if anything, has been said at other shows. Nina continues to beckon the audience multiple times to tell her the name and eventually someone says “Colin Kaepernick.” I want to assume that most people know who Colin Kaepernick is, but given the demographic of most regional theatre audiences, I’m almost certain that the majority don’t.

as a playwright, I often feel pressured to keep up with current events in my writing because I feel that it’s my duty to reflect the world I live in. I think, however, that this particular reference is too current, and it almost seems out of place because so many other protests of a similar nature happened during Nina’s lifetime and prior to Kaepernick. the commemoration of his efforts seemed a bit premature.

we return from Liberia by holding hands with our neighbors in the audience— yet another call for participation I wished wasn’t part of the show— and once we arrive back in the US, Nina continues to address pop culture.

she speaks about Halle Bailey being cast as Ariel in The Little Mermaid and Zoe Saldana being cast as ‘Nina Simone’ in a movie that was a limited ‘on-demand’ release in 2016 and never made it to theaters.

I think it was a great idea to have Nina address who has portrayed her in movies and tv shows, but I wished the playwright had used this opportunity to go more in depth about Nina’s looks and the whitewashing of Hollywood. in Nina’s discourse about Zoe Saldana, she asks the audience to pull out their phones and take a picture to capture what she really looks like.

as beautiful as Rabun is, she looks nothing like Nina Simone.

it makes me wonder if there is truly a shortage of dark skinned, wide nosed, actresses (there isn’t) because I have yet to see anyone portray Nina Simone that actually looks like her. I would love to see this part of the play expanded and explored, but again, I worry that it will change the tone.

the play ends. Rabun has done a wonderful job with the task at hand, Craft has written a dynamic one woman show, and Hunter-Williams has successfully brought it to life. after the bows and applause, there is a reprise of ‘Young, Gifted, and Black’ in which Rabun asks the audience to clap and sing along if they know it.

no one sings along.

I’m not sure if that’s because no one knew it, or if they, too, had grown tired of participating.

or, because most of the audience was the exact opposite of ‘young, gifted, and Black.’

on August 25, 2019 in Hillsborough, NC, about thirty minutes from the almost entirely white, elderly audience at Playmakers, a KKK rally is being held in front of the courthouse.

Playmakers, on the campus of UNC Chapel Hill, where a history of racism and discrimination is embedded in every building, and white students burn cars in the street after winning basketball games.

this was about Nina, but the context is important too.