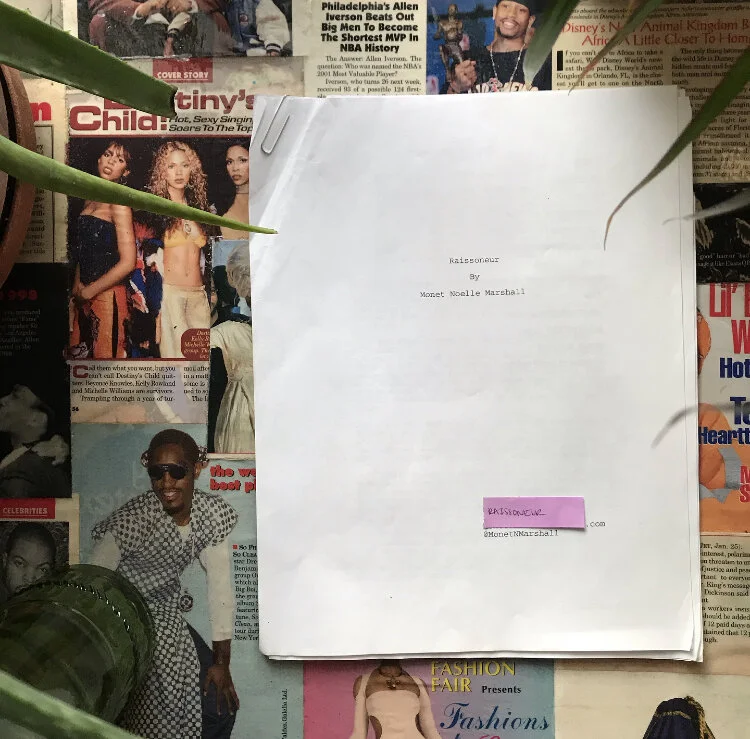

'Raissoneur'

I am a proud play thief. I have a knack for finding abandoned scripts and if no one claims them, I will happily take them home. no shame. I love theatre and I don’t think the ingestion of plays should be limited to productions. playwriting is literary— we should be reading plays.

I found Monet Noelle Marshall’s Raissoneur in the theatre office at NCAT two years ago right after completing my degree. I was very excited. from what I know of Marshall’s work, it is immersive, experimental, and non-traditional in all the best ways. Raissoneur was no different.

the stage is empty when the play begins, and Robyn, the central figure of the play, immediately breaks the fourth wall and talks to the audience as if they are old friends, leaving the stage to pass out biscuits. in this opening scene, Marshall is foreshadowing the audience’s role in the play and establishing the immersive nature of the piece.

almost immediately after Robyn tells us that the play is a one woman show, she is interrupted by Professor, who names Robyn as the play’s raissoneur. as Robyn protests Professor’s claim, her one woman show is overrun by the remaining characters: Mama, Diva, Sunshyne, Big Black Mamba Shakur X, and Kid.

in an accidental blackout during the first scene, Robyn disappears, and the rest of the characters split up to look for her around theatre. the characters are paired off to conduct the search for Robyn: Mama and Diva explore the dressing room, Sunshyne goes with Big Black to look for Robyn in the green room, and Professor stays with Kid on the stage

the pairing of these characters is important. in fact, it is the paring of these characters that finds Robyn.

Mama and Diva are used to show conflicting ideas of Black womanhood. these characters could be loosely identified as the mammy and the jezebel, but Marshall doesn’t adhere to these stereotypes and instead shows us how dynamic a Black matriarchal figure can be. typically, the Black matriarchal figure is portrayed as non-sexual and in perpetual servitude, but Marshall has transformed this figure by making her the object of Diva’s desires. the audience gets to see the Black matriarch as a sexual being, with her own wants and desires outside of nurturing her children. the pairing of Mama and Diva in the search for Robyn, allows Marshall to explore conflicting identities and provide commentary on the suppression of queerness in Black women. both women admire each other, coveting their perception of the other’s life: Mama wants Diva’s confidence and independence, and Diva wants Mama’s stability and assurance. their exchange in the dressing room brings them together, almost to a kiss, before they are interrupted by Kid, who has found Robyn.

Big Black Mamba Shakur X and Sunshyne are used to articulate differences in social ideologies. Big Black represents the anger, frustration, and Black nationalism that is often associated with being pro Black, while Sunshyne, a white woman, represents peace, sacrifice, and softness.

the racial differences between these characters made this part of the play very frustrating.

in scene three, Big Black (whose barbaric characterization requires him to tote a spear, dagger, and flashlight), cuts his hand as he attempts to put his dagger away. when he cuts his hand, Sunshyne springs to the rescue, removing her shirt to create a tourniquet to stop the bleeding. as Sunshyne and Big Black decompress from the excitement of his injury, Big Black says:

BIG BLACK. You’ve got some Black man’s blood on your hands. Bet its not the first time. (Marshall 19)

Sunshyne immediately responds with a monologue in AAVE/Ebonics, exhibiting a very different speech pattern than the one she previously used, going as far to actually call Big Black a ‘nigga.’

(a white girl saying nigga...)

she cusses at him and excuses her behavior by claiming to be from the South Side of Detroit. they kiss passionately, he slaps her, and then he curls into a ball and begins to sob. Big Black tells Sunshyne his real name, and shortly after, they are interrupted by Kid, who has found Robyn.

the ending of scene three reminds me of the end of Slave Play. there is an interracial couple, a sexual exchange, violence, sobbing, and somehow, everything is okay in the end. though the racial differences between these characters make this scene troublesome for me, these characters are extremes, with characterizations that are meant to emphasize their differences.

by now it is clear what Marshall is doing: the characters are paired off in a way that allows for the juxtaposition of thought processes.

but the name ‘Sunshyne’ to denote the only white character in the play is very odd to me. and I don’t think it is necessary for Sunshyne to be white to show an extreme difference between her and Big Black.

I often wonder when reading Black plays with white characters if it even makes sense to integrate the realm of the Black play, and what purpose the white character actually serves in the space. is it imperative for Sunshyne to be white? does her whiteness add anything? would this scene still be powerful and make sense if Sunshyne were a Black woman?

I think so.

Robyn is found sitting amongst the audience. by the time Kid finds Robyn, he has coaxed Professor into breaking almost all of the traditional theatrical rules. this is another example of opposing viewpoints coming together. despite Professor’s protests for Kid to adhere to traditional theatrical standards, Kid has not only broken the fourth wall to search for Robyn, but he has also challenged many other standard, conventional practices like bringing audience members on stage and turning fullback. Kid’s ability to play with and in theatre is reminiscent of Robyn’s informal introduction in the first scene, and emphasizes the theme of theatre being an experimental projection of the playwright— it can be anything you want it to be.

after Robyn is found, she returns to the stage and a projection begins, showing a short film of Robyn opening a medicine cabinet in a bathroom and taking ibuprofen. when she closes the medicine cabinet, we see all of the characters standing behind her as she looks in the mirror. these characters are all a part of her, and they had to come together for her to be found.

it was a one woman show after all.

Robyn was the play, and the play was the raissoneur.

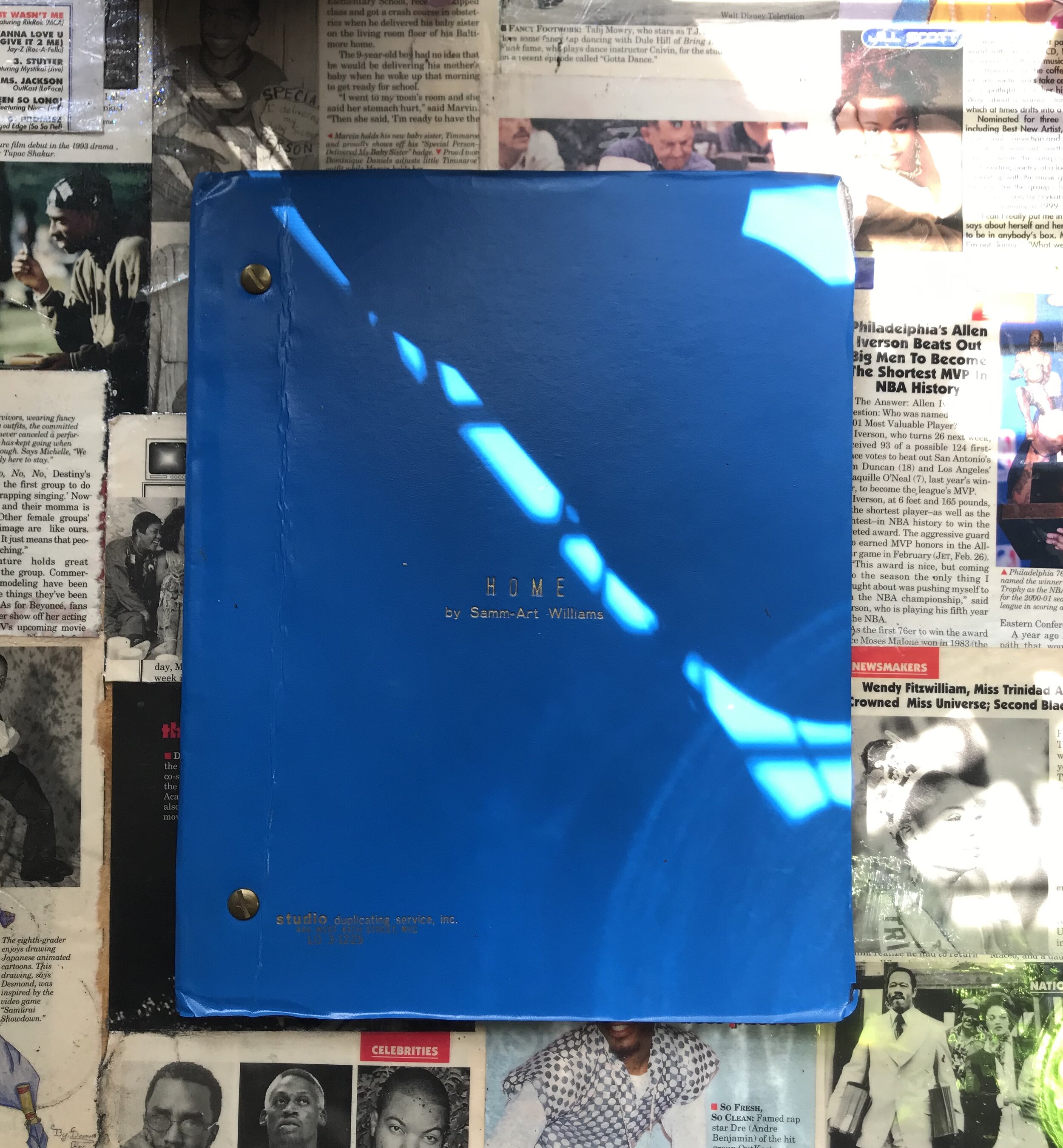

'Home'

most Black men do not write for Black women.

some evade writing for Black women by simply creating storylines that can exist without them, while others do it more tastefully.

August Wilson does not let his Black women talk to each other.

Tyler Perry’s Black women have to suffer.

and most of the Black women in Samm-Art Williams’ play, Home, do nothing but antagonize the main character, Cephus.

the play features an ensemble cast of two women, and one man. it is my understanding that ‘Home’ is a comedy. while phrases like “chocolate-coated quaaludes” and the absolutely ridiculous portrayal of women did make me laugh, I’m not sure that was the playwright’s intention.

contrary to what I found commonly accepted on the internet, the script states that the play begins in Cross-Roads, North Carolina, where Cephus was born and raised. all Cephus knows and cares about is the land, and when he is drafted for the Vietnam War he does not go. as a result he is jailed, and loses everything— including his family farm— while he is away. after being released from jail, he moves north to a “very, very large” city. he finds work, but is almost immediately fired for lying about his criminal record, and finds himself homeless, living on the streets. after a brief while, Cephus magically receives a letter saying he should move back to Cross Roads because someone bought his farm and put it in his name. Cephus returns to the farm, goes on and on about how much he missed it, and adjusts to the changes that have been made in the south since he’s been gone.

at the end of the play, it is revealed that Pattie Mae bought the farm for Cephus.

Pattie Mae, Cephus’s primary love interest, left Cephus to go to school in Virgnia at the beginning of the play. she stays in contact with him for a little while, before delivering a lengthy speech about how she has “outgrown the land.” she gets married, moves to Richmond, and begins to exist in another realm, only appearing in the play as a figment of Cephus’s imagination, until it is revealed that she purchased his farm at the end.

I think it’s absolutely ridiculous, but according to Williams’ script, it was Pattie Mae’s dream to be with Cephus and make pies for him. and there is nothing wrong with wanting a humble country life, this is just odd because Pattie Mae explicitly says the “socioeconomic conditions” of the rural south aren’t up to her standards. she was in love with Cephus, but when she left Cross Roads, she married a lawyer and her lack of communication with Cephus would allude to her being content with her new life. not sure why she would come back.

with the exception of Pattie Mae, the women Cephus engages with during the play, romantically and otherwise, are only mentioned or actualized to perpetuate trauma. when Pattie Mae goes to college, Cephus “takes up” with his second cousin, Pearlene, and though she eventually leaves him for a marine, the rest of the women in his family jealously chastise him. when he goes to jail, his Aunt Hannah sends him a letter delivering nothing but bad news and notices of death. then Cephus moves north, and Myrna does her best to take all of his money.

Pattie Mae is the only woman in the play that isn’t awful and even she is questionable.

in contrast, the men are extended an immense amount of grace. all of the characters are heavily flawed, but the male characters seemed to be more fully developed. Cephus recalls and shares several memories throughout the script, and Williams uses those stories to expound upon the nature of the male characters and how they have positively impacted Cephus, despite their downfalls. by presenting these characters in past tense as memories, there is more room to recall multiple aspects of their personalities. the women in the script are presented in a present tense, giving Williams very little room or time to do much else than vilify them, because that’s how Cephus saw them at the time.

my favorite thing about the play is the poetic nature of the language. it is clear that Williams understands Black rhythmic speech patterns.

the copyright for Home is 1978, and it was nominated for a Tony Award in 1980.

what does that say about the way Black women are perceived?

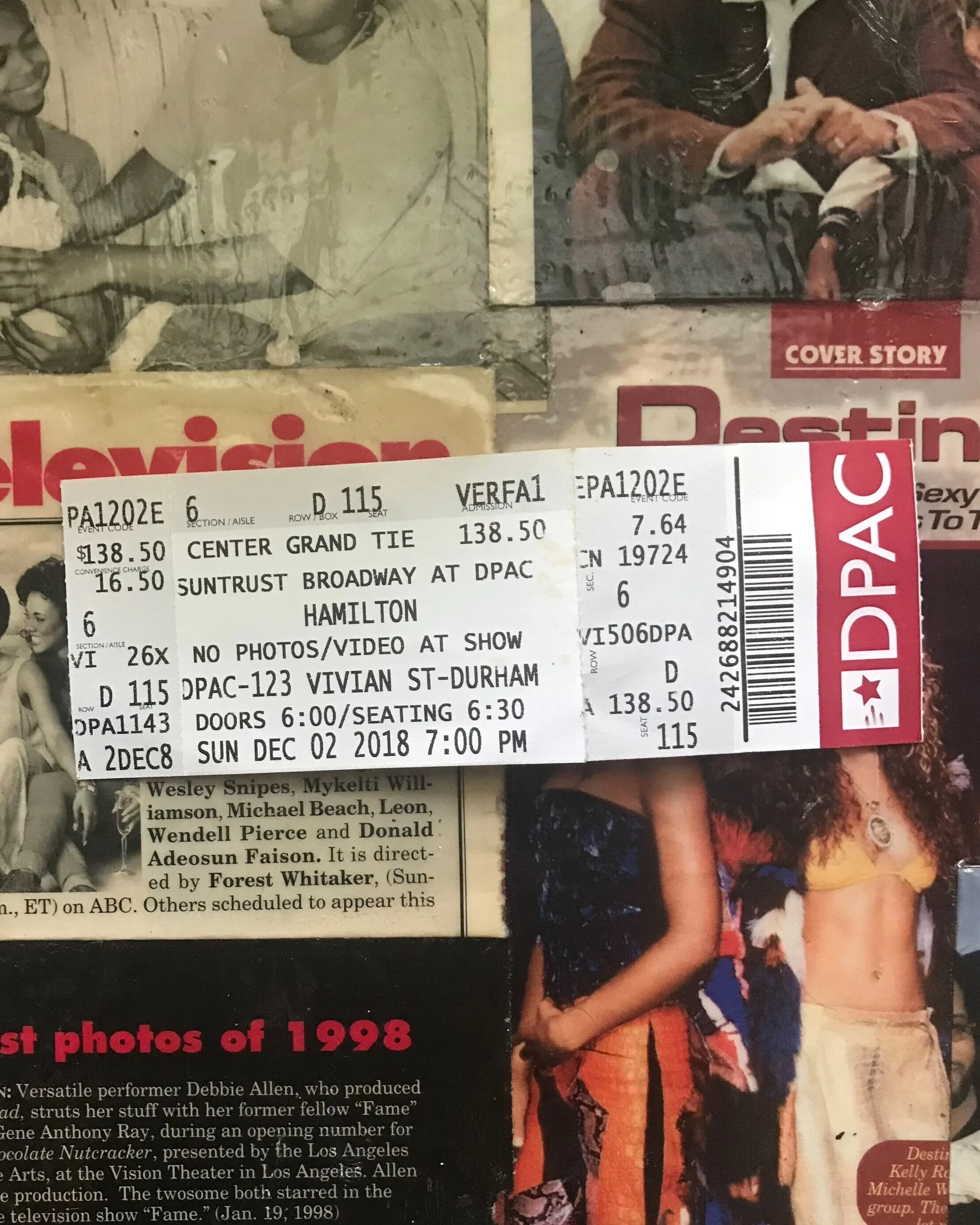

‘Hamilton’: a study guide

some context:

Hamilton (@ the Durham Performing Arts Center/in theatres)

you’ve heard about the show. as a former musical theatre major and enthusiast you were familiar with a few of the songs, the general premise— it’s all the rage in your circle.

especially for Black actors. it was the musical we’d all been waiting for.

(read: jobs. employment.)

you liked In the Heights and yet, the music for Hamilton never really grasped you.

(I blame the content)

but here you are. getting to see Hamilton in your hometown.

you walk up to the theatre thinking about the times you performed there during high school. that one dance rehearsal on the second level.

the hole in the dressing room wall.

the red carpet.

the jail across the street.

you can’t help but notice the police presence outside the theatre.

the k-9 unit.

(you start thinking about what you did before you got there and though it’s been hours, your palms get sticky)

you’ve been to this theatre before. you’ve performed here! but the metal detectors at the doors are a surprise.

as you help your parents remove keys and coins from their pockets, and place your bag in a bin, you can’t help but ask why.

the venue deflects, saying the increased police presence is at the request of the touring show.

and you,

being you,

elaborate that you find it odd. you’ve only seen these security measures taken when a show is intended to attract a diverse (read: nigger) audience.

but you understand that it is not something that the older Black lady patting you down can control.

and though you are shaking,

(you are angry)

you thank her and make your way to your seat.

for your consideration:

parallels between light complexions and characters in positions of power

the role colorism plays in desirability

songs that seem to make sense for the person singing them (thinking about the content and context)

juxtaposition between Burr and Hamilton— how does the color dynamic affect your interpretation of the situation? (or does it at all?)

juxtaposition between Angelica and Eliza — would Angelica be as effective if she were more similar in appearance (lighter?) to Eliza?

if every character in this play were white (as they are in real life) would you still enjoy it?

final thoughts:

at what point does the musical Hamilton become an exploitation of Black and Brown aesthetics in an effort to popularize and commercialize a white story?

does this reality exist when the playwright and creator is Brown himself?

is it possible for a Brown playwright to exploit his own narrative for commercial success?

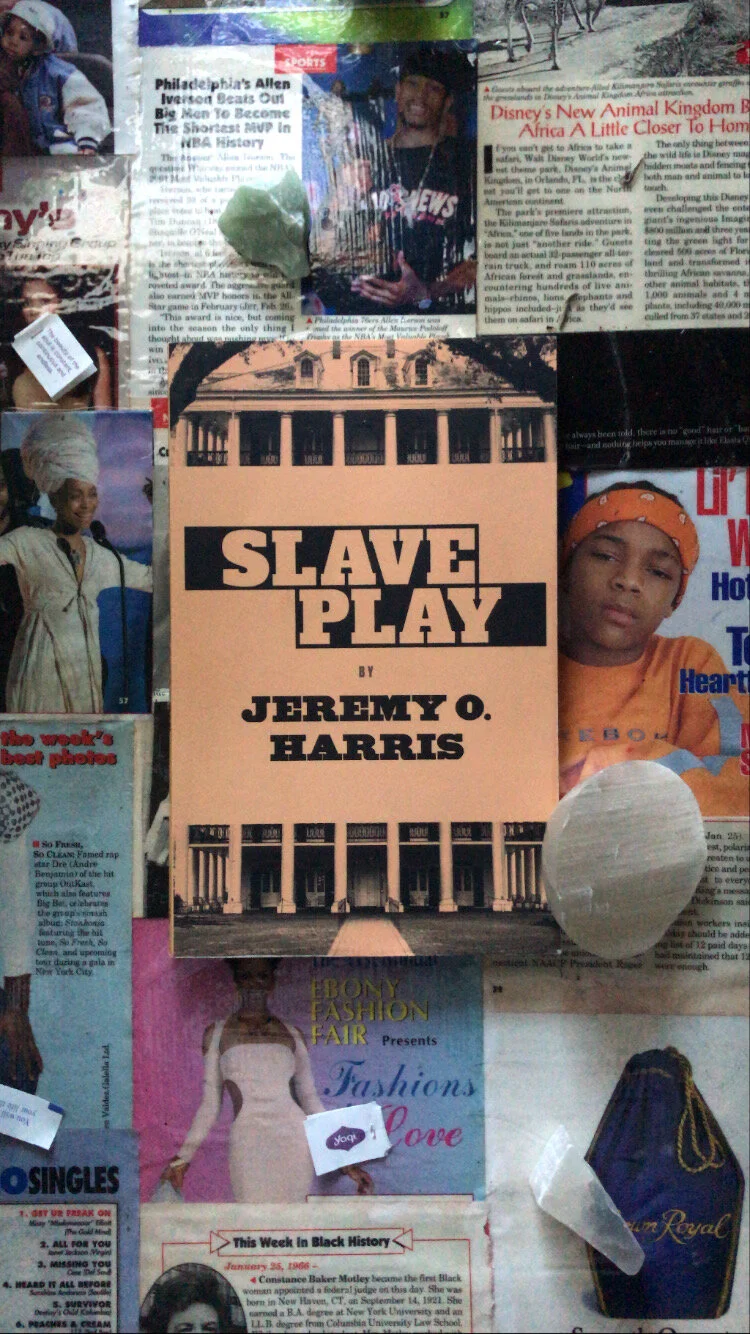

'Slave Play'

it is much more difficult to critique a script, than it is to critique a live performance. when you critique a live performance, you can only critique what you’ve seen. you don’t have the playwright’s notes, character descriptions, or stage directions. when you critique a live performance, your critique is contingent upon the actors, the director, the costume and set design. but when you critique a script you have only the playwright’s words and your imagination.

the play becomes a creation of your mind.

in 2019, one of my old college professors tweeted an article about Jeremy O. Harris’s Slave Play. it was not positive. the discourse that surrounded the tweet, mostly by scholars of African American and Africana Studies, seemed to be stuck on the optics of it all: sex, race, slavery, violence— the title alone would send anyone’s mind into a frenzy.

but that’s what I love about it! someone was finally making real theatre— theatre that made people uncomfortable, theatre in it’s best and purest form. the title’s ability to startle and outrage warranted my constant defense of the piece, and I defended it, even though I hadn’t seen the play or read the script.

at first, I thought the play was about slavery and sexual role play. then, I thought the play was going to be about interracial relationships and power dynamics. and to some degree, both of those are true.

Slave Play is about the inability to explicitly talk about, accept, and analyze racial differences.

in the first act, three couples are participating in a ‘Fantasy Play’ for Day Four of an Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy at the MacGregor Plantation in Virginia.

this is where most people stop.

when we meet the couples, they are role playing as inhabitants of the plantation. I’ve heard that people walk out of this play, and I can’t say that I don’t understand that. Harris is attempting to bring attention to a topic that many people would rather repress or will out of their awareness, and he doesn’t do so delicately. no one should be surprised that it’s painful for many people to see Kaneisha, a Black woman (and a slave for the sake of the role play), beg Jim, a white man (playing an overseer), to call her a “negress.” and I cannot shame people whose stomachs turned listening to Alana (playing ‘Mistress MacGregor’) sexualize Black men, essentially reducing them to a “large, Ebony dildo,” in the most graphic, heinous way. my stomach turned too.

Harris includes in the notes that this play is a “comedy of sorts” and should be played as such, but it’s easy to get swept up in the “fantasy” and forget the context.

during the first act, each of the Black characters are denied control in various ways. the imbalance in Jim and Kaneisha’s relationship is denoted by a preoccupation with semantics. when Jim stumbles over his words, praises Kaneisha, or tries to devalue his power, he is actually taking power away from Kaneisha. Kaneisha wants to participate in the therapy, and Jim spends the first act constantly denying her of the experience.

Alana does the same thing to her partner, Phillip (“a mulatto”), but under the guise that she is helping him.

and Dustin does the same thing to Gary.

Dustin is the only white person who does not take a role of power on the plantation during the Fantasy Play, acting as an indentured servant. using subtext and stage directions, Harris is able demonstrate Dustin and Gary’s commitment to the Fantasy Play. there are times in which the stage directions refer to Gary as ‘Nigger Gary’ and times when he is referred to as simply ‘Gary,’ giving insight to how Dustin views Gary in that moment. most of Dustin and Gary’s dialogue revolves around racial identity, and the exchange feels familiar, like both characters have fought this battle before. Gary wants Dustin to accept and acknowledge his power, but in doing so, he would have to admit that he’s white. after becoming fed up with Gary’s commitment to his ‘slave in charge’ role, Dustin does finally claim ‘white’ as his racial identity, and for a moment it seems that the therapy is working.

Gary comes, and then he cries. Dustin panics, but he does not use the safe word.

(in act two, we learn that Gary may have been experiencing a panic attack, one of the many symptoms of Racialized Inhibiting Disorder (a disorder that all of the Black participants allegedly suffer from).)

act two is my favorite part.

the Fantasy Play in act one is ended early by Jim, who yells the safe word in the middle of having sex with Kaneisha (who was really enjoying herself). act two operates as a group counseling session, where the couples are invited to share what happened during their Fantasy Play. the session is led by Teá and Patricia, graduate students, who also happen to be an interracial couple.

the white characters in this play— including Patricia, who is described as “light brown”— have difficulty accepting, acknowledging, and being accountable for their whiteness.

Jim is white but he’s British, so he’s not that type of white.

Alana is white, but she’s a white woman, so she’s not that type of white.

Dustin is white, but he’s not white white, so he’s not that type of white (or white at all).

and Patricia is brown, but her proximity to whiteness, as compared to her partner Teá (“a mulatto”), affords her the same power as the other white people in the play. Patricia claims to be cautious in regards to her power, but she abuses it repeatedly in act two, frequently correcting Teá and cutting her off when she speaks. the hypocrisy in this act is plentiful, and provides substantial comedic relief for those who may have needed it.

at the end of act two there is a power shift. it sort of rolls like a snowball down a hill, and it starts with a reminder that the therapy is intended to help the Black partner in the relationship. as the Black characters begin to speak about their experiences, they are able to obtain the power they’ve been seeking.

Phillip is able to tell Alana that she’s just as bad as a white man.

Gary is able to tell Dustin that he’s sick of his shit.

and Kaneisha is able to tell Jim that he’s a virus, ending the act with a scream.

then there’s act three.

I read act three multiple times, and I still may have missed the point completely.

Kaneisha delivers a monologue to Jim, further elaborating on the ways in which he is a virus. she tells the story of how they met, of childhood field trips to plantations and when their sex life began to go downhill, ending by announcing her receipt of her ancestors’ approval to sleep with a white man.

so like I said, I read it multiple times.

as Kaneisha gives this monologue (solid audition material), Jim is massaging her hand, sucking her fingers, and taking off her shirt. as she reaches the topic of her ancestors approval, Jim interrupts her, telling her to shut up and finally calling her a “negress.” he proceeds to have sex with her in such an intemperate, forcible way that she has to claw him off. when she’s able, she yells the safe word.

she cries. she laughs. he cries.

and at this moment, the stage directions direct the actress playing Kaneisha to do whatever she feels is right before thanking Jim for listening.

for the sake of my understanding, my imaginary Kaneisha kisses Jim before thanking him. I also think a slap would be fun, but as I think of more actions for Kaneisha to take, I become more aware of how important this moment is to the understanding of this act, and the play in it’s entirety.

theory 1: Kaneisha finally gains power at the end because she gets what she wanted. Jim finally commits to his role.

theory 2: Jim went too far. what he did wasn’t a part of Fantasy Play.

there is a lot of evidence in the play that supports theory 1, but I still have a hard time reading the description of Kaneisha and Jim having sex in act three as sex.

I have to be reminded that this is a “comedy of sorts.”

I read the play twice, and I’m fine until act three. I keep getting tangled up in specifics, the semantics, the optics— it’s very easy to do. words are poignant.

this critique barely scratches the surface of Slave Play. I can tell you what happens in the script, I can identify the devices Harris uses to share his message, but to truly understand this piece, you will have to read, feel, and process it for yourself.

and even then, you still may not get it. maybe you have to see it.

a script leaves a lot to the imagination. and Slave Play is no exception.

I find myself wondering how the music affects line delivery and tone.

wondering if the choreography for sex and fights is always as graphic as described.

wondering how the ‘color’ or ‘shade play’ that Harris suggests when casting impacts the overall message.

(wondering if directors will even acknowledge this note.)

wondering if the scholars and academics ever got past the first act, and if they did,

wondering what they made of the third.