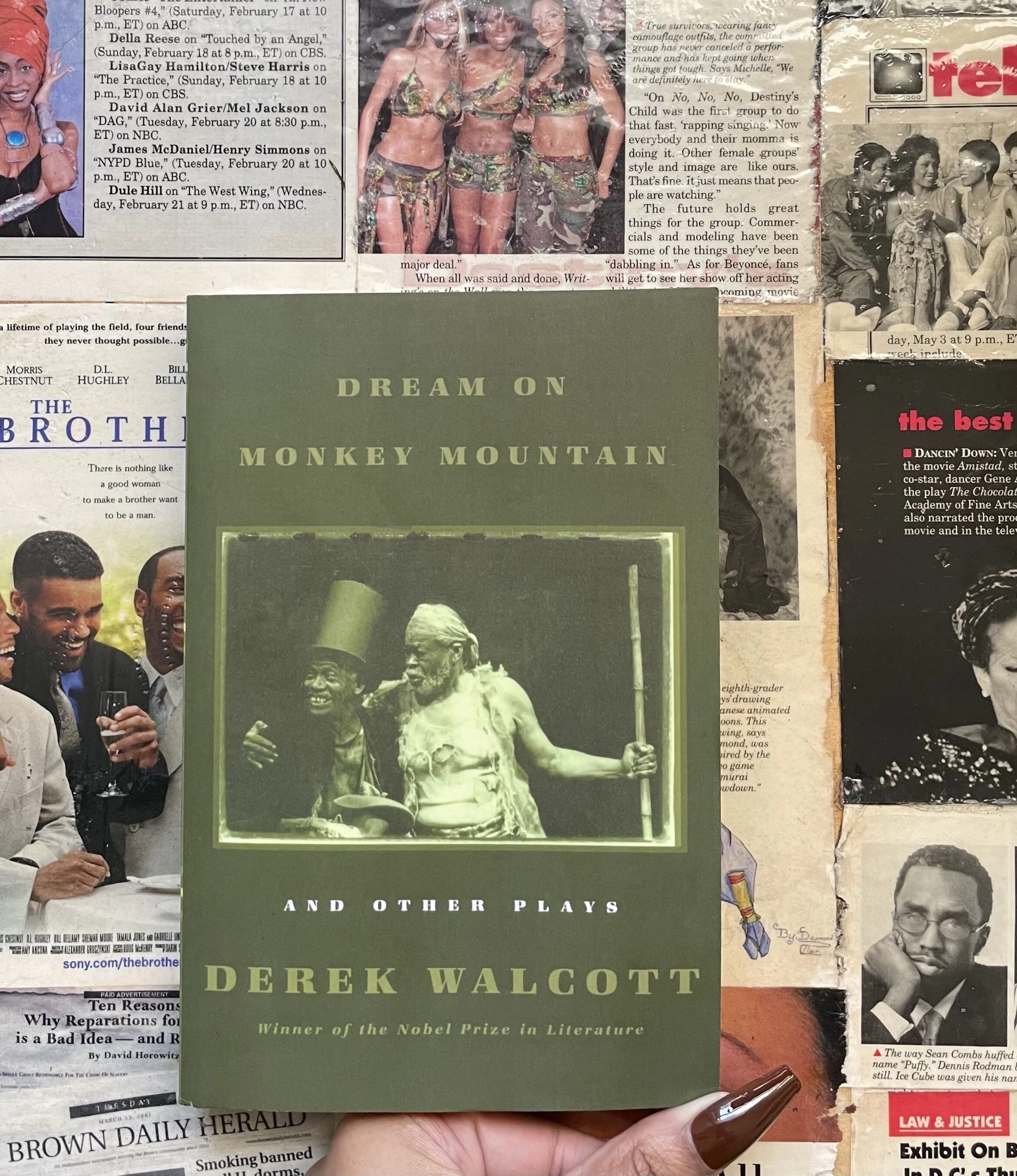

'Dream on Monkey Mountain'

I’d be lying if I said reading Derek Walcott’s Dream on Monkey Mountain was an easy task.

I started and stopped and started and stopped and kept on starting and stopping until I realized I had no idea what was going on.

this text required uninterrupted focus.

in the production note, Walcott describes the play as “illogical, derivative, [and] contradictory.” (208)

if you blink (or rush and try to read it in spurts), you might miss it.

Derek Walcott’s Dream on Monkey Mountain is a critique on colonialism in the Caribbean. and though the island on which this play takes place is an amalgamation of Caribbean islands, the sentiments echoed by the characters in this play are common thoughts in the minds of colonized peoples everywhere.

Walcott frames this study as a dream, using figures from Trinidadian folklore and Haitian voodoo to articulate the role race plays in colonialism and as a result, Black exceptionalism. the majority of his characters are named after animals or insects, and the characters in positions of power are given names that allude to white ancestry or influence. in doing this, Walcott is able to emphasize the divide between the colonizers and the colonized, denoting the roles each character plays in this hierarchy.

the play is not linear in structure— it starts in the middle, jumps to the beginning, and then pushes through the middle to the end.

I’d say the majority of the play is a dream, but Walcott has carefully blurred the lines making it almost impossible to determine what is a dream and what is reality.

in the play, Makak has a dream in which an apparition of a white woman visits him. the apparition declares that Makak is of some royal, hierarchal status and convinces him to leave Monkey Mountain to travel to his home, Africa. Makak, along with his friend Moustique, set out for Africa performing ‘miracles’ along the way. at some point, Makak is arrested for disorderly behavior in a market and Corporal Lestrade brings him to jail where he is housed in a cell alongside Tigre and Souris.

Moustique refers to the apparition Makak has seen as la diablesse, a demonic character in Trinidadian folklore that casts spells on vulnerable male victims. by personifying la diablesse as a white woman, Walcott begins to craft a metaphor for colonial influence on Caribbean islands. her whiteness gives her words validity and Makak succumbs to her wishes without question, referring to himself as her “warrior” and revering her as God.

the relationship between Makak and la diablesse is also used to introduce the theme of exceptionalism. she calls Makak by his ‘proper’ name, Felix Hobain, and instills in him a feeling of superiority by telling him he is from a lineage of African kings and lions.

at the end of the play, Makak struggles to sever ties between himself and la diablesse, even though it is necessary for his freedom, because she has empowered Makak by making him feel special. Corporal Lestrade, described in the list of characters as mulatto, is the force that convinces Makak to slaughter la diablesse, continuing the conversation of exceptionalism in the nuanced realm of mixed race, colorism, and the resulting social hierarchies.

Walcott continues to establish metaphors for the effects of colonialism throughout the play in pointed mentions of the full moon, white spiders, and a white mask. he establishes the lore regarding these images, and gives the audience permission to associate whiteness with death.

and though Walcott makes the connection between colonialism and death painfully clear, he also takes the time to explore the journey of self-discovery in a colonized land.

Makak’s desire to travel to Africa is framed as a pilgrimage, but Walcott wills readers to consider the distance between Makak and the continent. in his journey to Africa, he sacrifices his friendship with Moustique, denouncing its existence, and forming new relationships with Souris and Corporal Lestrade. when Makak mentions Africa in Part Two, Tigre conflates Africa with Monkey Mountain, and the revelation is made that Makak should actually be returning to Monkey Mountain, as that is his home.

Tigre: I’m a criminal with a gun, in the heart of the forest under Monkey Mountain. And I want his money.

Makak: Money … That is what you wanted? Thats is what it is all about … money?

Tigre: Shut up! Africa, Monkey Mountain, whatever you want to call it. But you first, father, to where the money buried. Go on. You too, Lestrade. Walk. (303)

there are many gems hidden in this text that can only be discovered through thorough investigation of language.

reading this text required research. there is meaning in the names of the characters, in their descriptions, in the folklore referenced, and in the methodical use of French.

there is so much to unpack.

Walcott suggests that the thoughts presented in this play “[exist] as much in the given minds of its principal characters as in that of its writer.” (208)

and in doing this, he gives his audience a foundation on which to self assess.

the desire to be exceptional, to save your people, to be the ‘chosen’ Black person, is the result of a colonized mind.

freedom for all cannot be achieved by one.

'I Hate It Here'

I do not like rushed theatre.

you can always tell. the story is disjointed/it appeases the audience in a way that sacrifices authenticity/there is little to no point.

a lot of commissioned works end up like this.

there is a strict, maybe even impossible deadline/requirements that the script just doesn’t meet/rules and restrictions that inhibit your creativity/and an audience that you don’t identify with that you must appease.

sometimes, commissioned work just doesn’t come out the way you hoped it would.

Studio Theatre commissioned Ike Holter’s I Hate It Here: Stories From the End of the Old World in response to the pandemic. the play is offered for free via Studio Theatre’s website (through March 7, 2021) and is described as a “mixtape” comprised of stories that are supposed to reflect what’s happening right now (protests, pandemic, pandemonium).

when I think about a mixtape, I think about a cohesive project. I think about tracks that are tied together by some theme or dj or artist/there is always some sort of glue that holds it all together.

the use of a ‘mixtape,’ in this case, refers only to the episodic nature of the play and organization of the scene breakdown.

the play starts with a song.

(I did not need a song)

and it ends with a song.

(the same one)

and I think that speaks more to the play’s commercial appeal than it is a strike against the playwright.

I often found myself more curious about the circumstances under which this play was created than the content of the play.

there were many scenes that felt inauthentic/there were many scenes that felt forced, coerced and for a very specific audience.

needless to say that audience wasn’t me.

and while I do think the piece is very ‘now,’ I think the very notion of it begs us to question what ‘now’ means when creating.

what does it mean to be current/how do you keep up with the times?

you create in new mediums but what is it about?

do you poke at the traumas and re-enact pain?

or do you create to help push forward and through?

there were standout scenes/scenes that felt real and poignant. but, as a Black woman, I felt like the majority of the play picked at very fresh wounds.

for others, however, this may have been refreshing. I am not Studio Theatre’s audience, and I can see how this may be both an enjoyable and unsettling experience for them, a juxtaposition that appears to be the current trend in popular theatre.

it was clear that this was a commissioned piece and may not actually reflect the artistic ability of the playwright. well, to me it was.

what do you think?

listen to Studio Theatre’s I Hate It Here: Stories From the End of the Old World by Ike Holter until March 7, 2021.

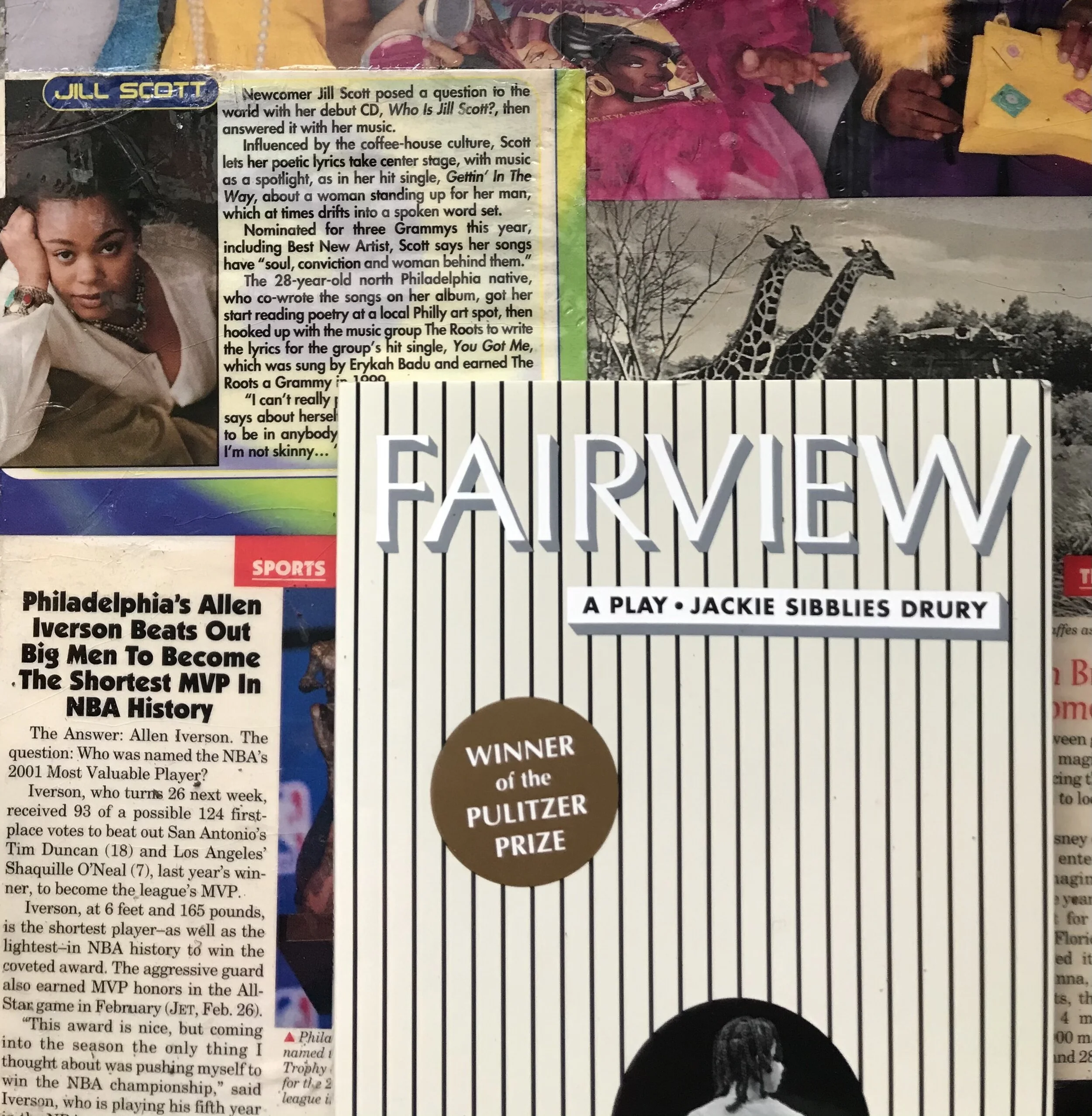

'Fairview'

I’m starting to see a bit of a theme.

I may be wrong, but Slave Play and Fairview appear to have quite a few similarities.

both, plays by Black playwrights with great critical acclaim.

one, on Broadway, the other, off-Broadway (but close enough).

both rose to prominence in 2019.

in both plays, the characters deal with race head on. in fact, the plays center racial differences and dynamics.

both casts feature a set of white people who are ‘trying their best’ to be racially conscious and competent, but failing.

and both plays do that thing/that literary thing where they sum it all up in a lengthy monologue at the end.

the plays are both exciting to read. they are funny, they are fast paced/they rile/they excite/they do all the things we want a play to do.

but something’s off.

consider: Fairview seems to perpetuate the theme it is attempting to critique.

I want to be clear as I begin this critique: I enjoyed reading Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Fairview. but I also enjoy roller coasters, and true crime podcasts, and psychological thrillers. I like to go on a ride when I read plays— I wanna feel something!

and Fairview made me feel… a lot of things.

prior to reading, I understood the concept.

in act one, we watch what ‘appears’ to be Black family preparing for their mother’s birthday dinner, but it is clear that this family is being watched.

in act two, we meet the people that are watching them.

in act three, the people watching merge with the people being watched, becoming members and friends of the Black family.

from the conversation in act two, one can only assume that everyone watching is white.

the concept is like, BOOM, mind blowing. I’m into it cause I’m thinking it’s going to be suspenseful and intense and/it was all of those things. it’s about living under the white gaze and rejecting the white gaze/reversing the white gaze/gazing back.

right?

before I read this play, I did my research. I wanted to see what the production staff looked like: who directed this? who choreographed this? who was the stage manager? were there Black voices present when this Black art was being created? were Black voices amplified and considered when bringing this Black art to life?

and it it looked like there were. there were Black voices present.

(the director was white)

in the first act, Drury makes it clear that this Black family is someone’s perception of a Black family. she uses words like ‘appears’ and refers to their home as a ‘set,’ describing it with broad adjectives such as ‘very nice.’

the family knows they are being watched.

there are little asides where they ‘fix’ themselves, looking into a fourth wall mirror.

there is overt foreshadowing present in the family’s repetitive remarks about their efforts to be presentable.

and if you needed even more proof that this family is performing under a watchful eye,

they shuck and jive. multiple times.

so, because these Black people are acting as if they are under a white gaze, a white gaze must be present. and having a white person direct this work makes sense.

right?

when the white characters are introduced in the second act, they are watching act one. as the Black family goes through the routine of act one for the second time, the white characters are taking turns to provide their answers to the question:

“… if you could choose a different race, what race would you choose?” (32)

here, in the second act, the Black characters act as props. the focus is on the white characters. their discussion erupts when one of the white characters divulges that if she could choose a different race, she would choose to be ‘African American,’ and recalls a story of a childhood caretaker in a very “I love my slave because it takes care of me” sort of fashion.

the act ends with a white man ranting about how oppressed he is.

…

when we reach the third act, and these worlds collide.

the white people fill in, performing their perception of their roles in and in relation to the Black family. and they wreak havoc.

they assert storylines to create drama within the family, suggesting drug use, gambling, poverty, and struggle though none of these things were originally a part of this particular Black family’s plight.

the play ends with a soliloquy, in which the daughter of the Black family, Keisha, asserts that if she could tell a story to ‘her people’ she would tell them the story of a person who got what they deserved/a person whose outcome was fair compared to their neighbors.

Keisha asks in the monologue:

“Do I sound naive?

Does that matter?

Do I have to keep talking to them

and keep talking to them

and keep talking only to them

only to them

only to them

until I have used up every word

until I have nothing left for

You? (103)

she says she’s talking to “colorful people/people of color.”

(I read the monologue a few times and I’m still not sure Keisha is talking to me.)

and to be honest, it feels like Drury has “used up every word” with the creation of this play.

it’s all for them. it’s all about them.

Drury is trying to correct them/she is teaching/she is attempting to make them understand.

and it feels like there’s nothing left for me.

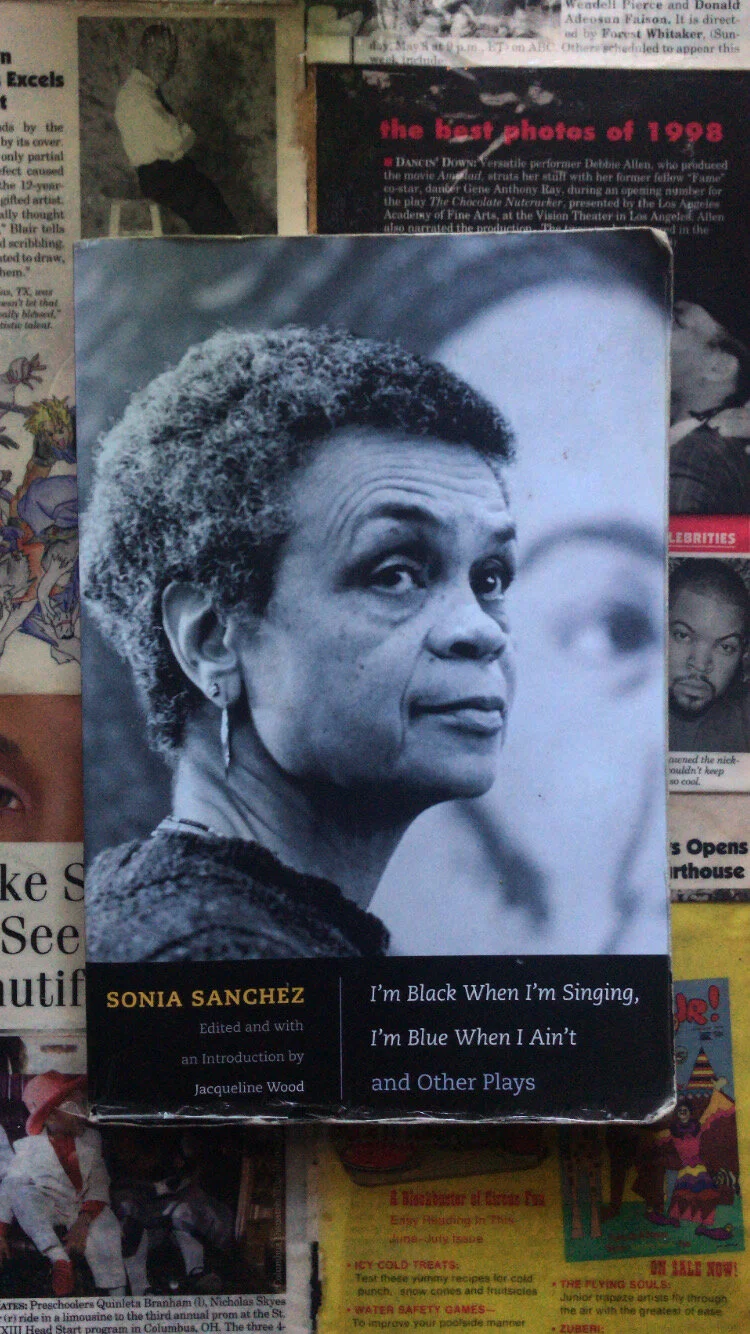

'Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us?'

it was very difficult to make this critique succinct.

I read the play/I read the introduction/I read the preface/I read the included essays.

I read the play again.

(I decided that I would circle back here in the future)

this is my critique of Sonia Sanchez’s Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us? at present.

Sanchez is my favorite playwright. her commitment to communal, accessible, inciting theatre has inspired the both the development and execution of my own theatrical works.

I first read Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us? when I was about seventeen.

reading this play again was not easy.

and it’s not supposed to be.

like most of the plays during the Black Arts Movement, Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us? is a call to action, directly targeting Black women. it is meant to disturb, to rile.

and if it were ever produced, or read, it would do just that.

this critique is just as much about the play as it is the erasure of Black drama.

though Sanchez’s wikipedia page suggests otherwise, in the anthology ‘I’m Black When I’m Singing, I’m Blue When I Aint and Other Plays’ by Sonia Sanchez edited by Jacqueline Wood, Wood asserts that this play has never been produced, only published in Ed Bullins’ The New Lafayette Theatre Presents. the play’s lack of production does not surprise me, but it did help me further define the criteria I use when critiquing plays.

my college audition monologue was from this play, and yet, there is not a single character (out of the seventeen available roles) that I would want to be cast as. as someone who has trained as actor, I can’t help but consider the psychological toll roles such as the ones presented in this play may have on actors.

in each scene, Black women are humiliated, mocked, belittled, and manipulated.

there is no escaping it. and that is the point.

the play is saturated with blatant disrespect and disregard for the condition of the Black woman, positioning Black men as the primary enactors of physical and emotional violence toward Black women.

I don’t know that I would be able to perform the actions of these characters in rehearsal everyday.

why can’t Black women play parts like Elle Woods? why can’t Black women have fun onstage? why must Black women constantly suffer?

I don’t believe in restricting the creativity of writers, and would encourage Black dramatists to write whatever characters they feel called to write, but I definitely think it’s valid to consider the impact a role could have on the mental and emotional health of Black performers.

I’d estimate the play’s run time to be thirty to forty five minutes. it is heavily rooted in spectacle, demonstrated by Sanchez’s frequent employment of sex and violence to articulate her message. the scenes depict the various ways in which Black women have been mistreated, each scene more painful than the last, and followed by dance numbers in which dancers illustrate the essence of the previous scene, simplifying the actions of the actors.

ultimately, the play is a critique on the oppressive misogynistic regimes implemented by the men of Black liberation movements. and it is necessary. but it does not need to be produced.

in the introduction of the previously mentioned anthology, Wood asserts that playwrights of the Black Arts Movement did not write with production or any other traditional theatrical ideals in mind, but she also goes on to mention that plays are effective vessels for social change because they don’t require literacy or privacy from the audience.

this makes sense in terms of performance, but considering that most of the dramas from the Black Arts Movement were published and not performed, approaching the creation of theatre with this mindset could easily serve as a hindrance. and it has.

Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us? should not be produced for many reasons, but most logically because it’s structure. with a cast of seventeen, it is very improbable that this show can be produced in an equitable way. there is also far too much that is left to the will of the director, and that alone can change the entire message of the piece. it’s not a task I’d want to take on without Sanchez’s involvement.

however, in terms of study, Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us? acts as a dissertation on the position of the Black woman in Black liberation movements of the late sixties and early seventies. though it is just as visceral, the play is easier to digest in written form, and a literary format allows the reader to take their time and process the examples provided. the path of analysis is basically laid out, as the scenes are almost coupled with corresponding dance numbers and by comparing the two, one should be able to begin to grasp the central themes of the work.

it should really make you quite angry.

but as the focus was not on literary success or theatrical performance, Uh, Uh; But How Do It Free Us? like many other plays of the Black Arts Movement, now exist to many as an irrationally angry phase of Black theatre. and many of the plays that were erected during this time have no record of occurrence.

the literary preservation of dramatic works is very, very important.

production isn’t always what it’s cracked up to be.